- Home

- Laaleen Sukhera

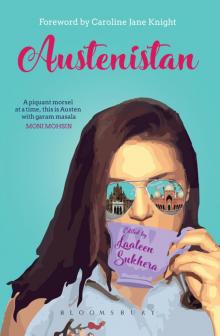

Austenistan Page 3

Austenistan Read online

Page 3

‘Leave?’ her mother said, as if she’d suggested something totally outrageous. ‘But the wedding’s only really starting now. I saw you dancing earlier with that Faiz Dar, why don’t you go and find him again?’ her mother said, refraining only from adding a cheeky wink.

‘Just keep an eye on Leena, Mama,’ Elisha said, sharply, before walking off in search of a sugary cola to fortify herself. The whole evening had been overwhelming so far.

Faiz wove his way through the crowd and found Saif, still engrossed with Jahan.

‘Let’s go,’ Faiz urged his friend.

‘Why? I’m having fun. Aren’t you enjoying yourself?’

‘Not anymore. I saw someone I just can’t stand who’s ruined my mood.’

Just then there was a momentary lull in the music as the DJ transitioned to more upbeat music, and Faiz’s voice carried to where Elisha was standing at the bar behind them. Looking pale and stricken, she assumed that having overheard her mother’s remarks and observing her sister’s behaviour, Faiz was leaving to get Bhatti away from what he perceived as a totally unsuitable family. When he avoided meeting her eye, she felt sure.

Dinner was announced and the guests started moving towards the tables covered with chafing dishes. Upset, Elisha needed a few minutes alone to clear her head and process her thoughts, so she left the marquee and went inside the empty house to use the loo.

Observing the long line outside the powder room, she ventured further inside the house hoping to find a vacant bathroom.

‘Young people nowadays are too much,’ an annoyed heavy voice said from the inner recesses of the house. Polly walked up, looking flustered. ‘I was looking for a clean bathroom, and I walked into a room with a group bent over the glass table with white powder on it. Dilawar with some boys and a girl also. People have no control over their children. Why would they behave like that and here? So openly. What’s the new generation become? Completely rotten!’

Recognising with a sinking heart the flirtatious giggle and excited high-pitched voice coming from the room Polly had pointed out, Elisha waited till the shocked woman had walked away before proceeding towards the room with dread in the pit of her stomach. No, she wouldn’t dare. This was too much. She tried the door handle, but it had been locked now, some sense had prevailed. But if people were to discover Leena locked in a room full of boys, they would assume the worst, regardless of the truth. She had to get her sister out of there, fast.

‘Leena, Leena are you in there?’

‘No, she’s not here.’ It was Dilawar’s muffled voice. ‘It’s just us. Do you wanna join us, Elisha?’

Not giving up, Elisha kept knocking till he, looking annoyed, opened the door a crack and popped his head out to see what was bothering her. She managed to wedge her foot in and spied her youngest sister.

‘Leena, what are you doing? Have you lost your mind? You come with me right now! Right now, you hear me!’

‘I’m not coming. You can’t make me.’

Elisha knew she only had moments before Polly would tell other guests what she had witnessed and they would show up, curious to see whose children were doing drugs, relieved that their own weren’t involved. But even with all her weight, she couldn’t open the door.

Suddenly, the door was shoved open forcefully and Dilawar reeled back. Faiz strode in, grabbed Leena’s hand and led her out of the room. Seeing how upset Elisha looked after she had overheard him, he had followed her to explain himself. Then he had heard the exchange through the door.

‘Your sister is waiting for you. I’ll deal with you later,’ he said grimly, turning in Dilawar’s direction.

‘Yeah, yeah, we’ll see,’ Dilawar said, but he looked scared.

‘She’s not even out of school,’ Faiz spat at Dilawar. ‘You’ve screwed up your life, leave her alone.’

‘He’s my friend. We were just hanging out. I didn’t do anything, Elisha, and he didn’t force me to come here. I followed him,’ Leena tried to play peacemaker and defended her friend, who appeared worldly and glamorous in her eyes.

Dilawar looked at Leena and then looked at Dar and was about to say something but thought better of it. He turned back to the table where the other guys were still huddled around, oblivious to the scene, focused on ensuring none of them should consume too much of the precious substance.

Faiz escorted the two girls out of the house back to the relative safety of the marquee thronged with people.

‘I’m sorry, Elisha. You worry for no reason. I wasn’t doing anything. I was just talking to those guys. Please don’t tell Mama and Papa or they won’t let me go out with Dilawar anymore. He’s not that bad, just misunderstood,’ pleaded Leena. Even their indulgent and somewhat careless parents would have a shit fit at this.

Elisha felt mortified that Faiz had to witness this ignominious scene. Her family had been exposed in front of him in the worst possible light. He probably regretted dancing with her earlier, probably regretted meeting her.

She could only hope to keep Leena out of Polly’s sight long enough so she didn’t recognise her and recount the story, adding salacious details to spice it up.

Faiz left the girls and purposefully strode off towards Saif who was still engrossed with Jahan.

Saif waved Faiz away, he didn’t want his tête-à-tête interrupted. But his determined friend pulled him aside for a private word.

‘Come here for a moment,’ Dar said firmly. ‘You need to find Jahan’s father and ask him to take them home. Dilawar’s being an asshole as usual. Ask Jahan to call him.’

By then, Elisha had brought her errant young sister to her mother’s side and was surprised to see Faiz approaching them. What could he possibly want with them now?

‘Elisha, I hope you don’t mind but I took matters into my own hands. Your father’s on his way to take you home. Don’t be too angry with your sister. Dilawar’s a born troublemaker. I’ve known him and his family for years. Just seeing him at parties makes me want to leave, he’s such bad news. Keep your sister away from him, she’s just a kid.’

Astonished, Elisha looked up at him, and smiled gratefully.

‘So, I’ll see you at tomorrow’s event then?’ Faiz said.

‘Yes, Mr Dar,’ Elisha said.

Begum Saira Returns

Nida Elley

“No character, however upright, can escape the malevolence of slander.”

—Lady Susan

As Saira Qadir entered the majestic tented pavilion set up in the front lawn of the Qureishi house, on the grand occasion of their daughter’s wedding, she knew that she was being looked at with envy, lust, or resentment. The lust was easily explained.

She wore an electric blue silk sari elegantly draped over a neon-yellow cropped blouse, custom-tailored by a hot young designer called Maheen K. A taupe Kashmiri shawl hung at her elbow, and a forest green Fendi dangled from her wrist. Emerald teardrop earrings hung from her lobes as a matching row of teardrops ran across the delicate tan skin of her neck. Her wavy, shoulder length hair had been blowdried stiff and sat like a dome above her, with sideswept bangs across her forehead. Whatever they were saying about Saira, it would not be that she wasn’t au courant. The golden dori tying her necklace together at the back of her neck snaked its way down to the middle of her back, where the hem of her sari blouse ended to reveal a sultry slice of flesh just above the waist-level folds of her sari. One might have thought it a bit much for an afternoon wedding, and in any other city it may have been.

Just one year ago, if Saira had made a similar entrance into one of the many social gatherings that took place every week in Lahore, men and women alike would have flocked to her side with hugs, side smooches, covert winks, and welcoming smiles. But today, on the first day of 1989, everything was different. She actually felt nervous making an entrance. She’d been dressing to the nines and attending parties since her own wedding twenty-two years ago. Her mother had been a great and gracious beauty, a fact she was only too aware of. Her you

nger sister hadn’t taken her looks. And so as a girl, all her mother’s hopes had ridden on Saira. She’d been painstakingly instructed on how to dress for various occasions, how to host a party, how to make the perfect cup of tea, and how to mask disinterest and converse with people she didn’t especially want to speak to. It was the period of exile leading up to this evening that made it feel rather like her first night out. And the fact that previously she’d always been accompanied by her late husband, Iqbal Rashid Qadir. His senior role at the bank had required them to attend a stream of social functions. Though he would have been much happier sitting in his study with a book, he realized the significant career benefit of being social, and more importantly, how much it thrilled his young wife. He’d have done anything for her, and it’s true, she had enjoyed being the belle of the ball. No one had been prepared for Iqbal to suddenly die of a massive heart attack at the age of forty-nine. Along with feeling his loss, she felt something else, she just couldn’t put her finger on it.

We have a woman prime minister, Saira thought, trying to look confident weaving her way through the scattered pots of burning coal warming the brisk January air inside the marquee. We have a woman prime minister, I can attend a wedding on my own, she repeated to herself. So much had changed in this last year, she’d been so taken up with the upheaval in her own life that she was only just absorbing it.

In August, President Zia had been killed in a plane crash; just a month ago, Benazir Bhutto had become the first female head of state of Pakistan, indeed, of any Islamic nation. The country felt alive with hope after a very long time. Saira guiltily felt touched by it even in her period of mourning. She’d never attended any of the protests against Zia; Iqbal’s family didn’t like that sort of thing. But her college friend Shahmeen was a journalist and very involved. When Shahmeen came to visit her last, she looked jubilant, sparkly with hope. She said more than anything she wanted the women-hating mullahs who’d protested Benazir’s win to finally sod off and bury themselves in the ground besides Zia’s grave. She hoped the country would reverse its backward trek into the dark ages, and take its place among the progressive nations of the world. It was hard to tell, Saira thought, looking around, if anything had moved forward or not.

She glided in the general direction of the main stage where the bride and groom sat. Heavily jewelled and made-up, the bride was anchored to her sofa by the sheer weight of her burnished bridal gown, covered as it was in traditionally embroidered dabka and edged with golden gota. The groom sat beside her with a goofy-looking smile, most likely, Saira thought, happy in the knowledge that he would never have to spend a sexless night on his own again. But she was not there to meet the couple just yet.

‘Tehmina, there you are!’ she said, greeting the mother of the bride, with the enthusiasm of seeing a long-lost friend. ‘I was looking all over for you. But, oh my, how stunning you look!’ She took a step back, looking her up and down, trying to look sincere in her admiration of Tehmina’s ridiculously full-skirted scarlet gharara. Typically, red was reserved for the bride, but, Saira thought, not today. ‘What a vision you are! You look like Tania’s older sister, much less her mother.’

Tehmina chuckled at Saira’s praise with delight. ‘Oh, Saira! Stop! You’re embarrassing me. It’s so good to see you. I’m so glad you could make it.’

‘How could I not? I still can’t believe Tania is getting married. It seems like it was just yesterday when she and my Masooma were playing with their Barbies and putting on fashion shows in our heels and saris.’ Saira’s expression softened as she thought of her daughter, Masooma, who was at college in the States.

‘I can’t believe it myself,’ Tehmina said, as she held Saira’s hands in both of hers and gently squeezed them. Spotting someone and jerking her head abruptly to the side, Tehmina begged leave to continue with her duties as hostess, ‘I’m so sorry, haan, I just have to check something. Do mingle and enjoy yourself. I’m really just thrilled you came.’ Her voice trailed off as she held up both sides of her voluminous gharara and tottered away on rickety heels. Saira watched her walking towards the buffet tables that were still being set up for lunch, barking orders at the waiters, who were all dressed in brick-colored shalwar kameezes. Some of them were skewering seekh kababs and chicken botis over a makeshift grill. Others brought out steaming silver dishes of lamb biryani and spinach paneer, while others moved jangling crates of Coke, Sprite, and Fanta glass bottles from the catering truck to the drinks table. Qureishi saab, who was himself, at that moment, taking stock of the lunch situation, walked up beside his wife and discreetly whispered something into her ear. Then he glanced back at Saira with a weak smile.

It seemed that ever since Iqbal had died, many of their society friends had collectively decided to shun her, while still publicly promising to be there if she needed them. She knew how hypocrisy worked, but it still hurt when someone you’d invited to your home every second week for twenty-two years, someone whose children had grown up with yours, looked as if they wished you weren’t there. And Farooq Qureishi, who’d once walked her to a secluded nook of his garden during a dinner party and shot her yearning looks till he heard the voices of other guests nearby.

A few years into Saira and Iqbal’s marriage, it had become clear that the wives of most of his friends and colleagues didn’t like her. She was vibrant and sexy, and she enoyed attention, none of which did her any favours in her social set. One night, at a dinner party at the Awans, Saira had been telling a story about her and Iqbal’s recent trip to London.

‘We had the most wonderful time,’ she’d said, swaying at the memory. It was the early 1970s and short shirts with fitted waists and loose shalwars were in fashion. Her tea pink shirt silhouetted her generous curves, while her sheer dupatta was tugged back against her neck, more a fashion accessory than an attempt at modesty. ‘We were staying with Iqbal’s younger cousin, Monty, who’s studying to be a chartered accountant. Now Monty, you must know, has decided not only to look the part of a Brit, but to sound the part, as well. So one night he asked us, in his heavily put-on British accent, whether we wanted to go to a “paahty”. Of course, silly girl that I am, I thought he was asking us if we needed to do potty.’ Some of the women giggled nervously while others backed away in disgust. This only made more room for more men to crowd around her and enjoy the show. ‘You see, he only had one bathroom in his flat, and if someone else needed to use it, they would have to run across the street to the petrol station. So I thought it was his way of asking us if we wanted to go before he went ahead and did so himself.’

The men laughed uproariously. She used her whole body to talk, exuding a charismatic energy. As the night wore on and she continued to hog the spotlight, some of the guests started to find her unbearable. Who does she think she is? Just because she’s young and pretty, she can get away with telling crass stories and making herself the centre of attention?

Rumours started circulating that the young bride was being too flirtatious with some of the other women’s husbands. Of course, nobody ever blamed the men, Saira thought, nor considered them capable of initiating these flirtations. Over time, Saira developed a reputation for being a little too candid. The rumours never found their way to Iqbal’s ears, but Saira always knew exactly what people said about her. The sniping didn’t bother her because Iqbal’s boundless love was her buffer against the lot of them. It had been such a heady feeling, living with a man who worshipped the ground she walked on, who spared no expense in making her happy, with the end result that now she had less of his savings to sustain herself than expected. It was a life Saira easily became accustomed to, and even though she never truly felt that she was in love with him, she loved him simply for being so good to her. Of course they said she’d ‘stolen’ him, as if he were an object to pickpocket with no will of his own. Iqbal had first been engaged to Saira’s older cousin, Sabrina, but while visiting his fiancée, he saw Saira and told his parents later that day that if he were to be married, it would be to

her and her alone.

Saira had kept a low profile all year. It was no hardship; she hadn’t been in the mood to attend lunches and parties without Iqbal. She had mourned his departure with the requisite humility expected of a widow, and she missed her friend, but now that a year had passed, she felt ready to move on. After all, she was only forty.

‘Darling! Over here! I’m over here!’ chirped a bulky woman with a short feathery crop inspired by Princess Di, dressed head to toe in gold organza.

‘Nina, thank God!’ Nina was her closest confidante. In a world of conformist phonies, Nina was exactly who she was, which was warm, honest, and blissfully without a sense of fashion. ‘What are you doing?’ she asked as Nina took her by the arm and steered her towards a corner where they could sit on a plush sofa and speak privately.

‘I just have to tell you…I saw the craziest thing. In fact, it’s so crazy, I’m not quite sure it really happened, but then, why would I be hallucinating? I have perfect 20/20 vision.’ Nina’s hands weighed down by ornate rings of all shapes and sizes, gesticulated wildly as she spoke.

‘Nina, calm down, what happened?’

‘I,’ she paused emphatically, ‘just saw Fakirullah Jahan, Mr Holier Than Thou himself, brush his hands against Samina Jatoi’s. It was not accidental. Can you imagine? After all the trash she said about you last week at her grandson’s aqiqa. Behaving as if you were Alexis from Dynasty, wanting to steal her husband. As if you would even entertain the idea of that crude, pot-bellied, balding man…she, of all people, brushed her hands against his and, I tell you, Saira, I tell you with 100% certainty, they exchanged a knowing look!’ she said, looking around to see if anyone had overheard her. ‘Uff, I can’t stand this place, and if I had half a chance, I’d move to the States and start life afresh with some bloody dignity. Which is what you should be doing!’

‘I told you,’ Saira said, ‘I told you there was something fishy going on there and you just didn’t believe me. But I knew. I knew it as soon as I bumped into both her and Fakirullah on the same day, at the same hotel. Anyway,’ she waved her hand in the air, dismissing the subject. ‘I don’t give a damn about these people and their little affairs. They can do whatever they damn well please. It’s really none of my business. But to turn around and then malign me? And for what? Because their sleazy husbands can’t keep their wandering eyes to themselves? What have I done, other than keep to myself this past year, and think only of my darling daughter and seeing her settle down?’

Austenistan

Austenistan